Seven in 10 Americans Feel Compelled to Connect…

Americans increasingly only interact with Americans who look, think, and live like them. Even so, there are some places and moments across the country where diverse, meaningful, and transformative connections are still happening.

More in Common is a nonprofit organization that tries “to understand the forces driving us apart, find common ground, and bring people together to tackle shared challenges.” Their researchers set out to understand what these look like and if we can scale up the models they provide. Over two years, the researchers engaged 6,000 Americans through national surveys, regional deep-dives, interviews, and focus groups in three mid-sized, demographically shifting cities: Houston, Pittsburgh, and Kansas City. These were chosen for their geographic diversity and the ways they reflect the broader changes playing out across the country. They describe their findings in a new report, The Connection Opportunity: Insights for Bringing Americans Together Across Difference.

“We were interested in how people are engaging or connecting with people across race, across class, across religion, and across politics,” explains Daniel Yudkin, a principal author of the report and the director of the Beacon Project. “Our main motivation was to just understand what are the barriers that are preventing people from doing this and how are people experiencing these connections or lack thereof in their own daily lives.”

Their findings explore opportunities to connect across four core lines of difference: race and ethnicity, political viewpoint, socioeconomic status, and religion. They found across all those areas, most Americans crave connection with people who are different from them, but they’re coming up against many barriers—most prominently, a lack of opportunities. The report makes a powerful argument for why we shouldn’t stop trying.

“In a world where we have very little opportunity to encounter people who are different from us, it’s just increasingly important to be aware of the effect that has on our perception of reality and our perception of other people,” says Ludkin.

Americans want to connect—some more than others

A majority of Americans, 70%, say they believe it’s their responsibility to connect across lines of difference. Two-thirds of respondents also agree that they can “learn a lot” from connecting with people who have different backgrounds and viewpoints than them, and many express interest in doing so more in the future. There were differences among social groups. Black respondents (74%) are always the most likely to want to connect, followed by white (71%), Asian (69%), and Hispanic people (64%.)

The reports quotes Bree, a 36-year-old liberal Black woman from Texas: “I definitely think that it’s good to get to know people with different outlooks because, if everybody’s outlook is the same, when does change happen? I definitely think it’s great to connect with people that don’t necessarily share your mindset.”

The report highlights an often-overlooked part of the story: the role of risk and safety. “Connection is not always simple,” Yudkin says. “It involves emotional, cognitive, and physical risks. There are areas in the U.S. today where it is not safe for members of minority groups and that can change what connecting means in terms of risk and what they aim to gain.”

Black Americans show the highest interest in connecting across differences, despite being the group that faces the highest risk when they do. For many, especially those in marginalized communities, connection isn’t just about empathy—it’s about survival. It’s about navigating a world where forging relationships across differences may be the best path to safety, inclusion, and representation. That depth of willingness—amid the reality of danger—shouldn’t be overlooked in stories about connection. It reminds us that while everyone faces barriers, the cost of disconnection is not evenly distributed. That said, across racial groups, most agree that greater racial, religious, and socioeconomic integration would make their community a better place to live.

As Lillian, a 32-year-old conservative woman from Texas, says: “I’ve been with people who I completely disagree with on basically every question on any ballot possible. But our kids are playing together. They’re having fun. Going to meet other people and just working towards the same project together, I think, can unify people, regardless of the differences generally.”

Contrary to the stereotype of religiosity breeding insularity, the research also finds that more religiously active Americans were more interested in connecting across all four lines of difference, including religious ones.

Why? One reason seems to be social norms. People actively involved in religious communities are more likely to believe that their peers value and engage in cross-group connection. The structure of religious life—regular gatherings, shared values, communal belonging—may give people both the confidence and opportunity to reach beyond their circles. This pattern held across denominations. According to the report, “conservatives” who frequently attend religious services are 12% more likely to be interested in connecting across difference than “liberals” who never do (58% vs. 46%)

Connection cascades

The report also finds that the more people engage in connecting with others who are different, the more they want to do it again. These experiences, which Yudkin termed “connection cascades,” suggest that initial engagement can lead to a self-sustaining cycle of further connection, if given the opportunity.

“For organizations who are trying to foster greater connection across differences, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you can create opportunities for people to engage in social connection, they might be more likely to do that again of their own accord in the future,” explains Yudkin.

One standout example in the research is the Dining with Purpose program launched by the Houston Food Bank. The Dining with Purpose program engages an intentionally diverse group of Houston residents to explore solutions over a series of engaging dinners. Serving Houston and southeast Texas since 1982, the Houston Food Bank is one of the nation’s largest food banks, providing access to 120 million nutritious meals. During the pilot stage of the program, the Houston Food Bank engaged 45 participants through 12 dinners; 9 in 10% of participants later reported feeling a stronger sense of connection to their community, a greater commitment to combating food insecurity, and an increased sense of belonging.

Most respondents to The Connection Opportunity survey identify extended conversation as the most common form of connection they’ve already experienced. But when asked what they most want to do, people overwhelmingly chose working toward a shared goal that improves their community.

That desire to collaborate—rather than just talk—suggests people are interested in building things with others, rather than simply discussing their differences. This insight challenges the traditional “dialogue across difference” approach. People aren’t craving hard conversations about identity—they’re craving common purpose.

The massive Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo offers residents of a highly diverse metropolitan area the opportunity to come together to celebrate a common local culture. In the three-week event, special programming is built in for days like Go Tejano Day and Black Heritage Day, which help attract a diverse set of volunteers. The Rodeo’s success relies heavily on its volunteer force of 35,000 people who contribute over 2 million hours of service, serving across 109 committees throughout the year. These diverse, dedicated volunteers show up, year after year, to plan events and engage meaningfully in their community.

The Rodeo has committed more than $600 million to youth and educational initiatives, including scholarships to over 2,300 students. In 2024, the event generated $326 million.

“For me, (belonging) is the economic opportunity,” says Edward, a 32-year-old politically unaffiliated Latino man from Houston. We’re a great hub for sports and also entertainment. I guess it’s just the mix of cultures. You’re able to see so many nice things from Southern American food to Latino. Even Asian cuisine is making a big impact here in Houston, as well. I think that’s why I think I see myself staying here.”

All this activity may shift attitudes, suggests the report, by fostering positive experiences of connection and heightening perceived community norms, triggering multiple “connection cascades.”

“At the rodeo, you just meet so many people,” says Dan, a 47-year-old liberal Black man from Houston. “Everybody’s working together. One common goal.”

Because of community events such as the Rodeo, Houston residents are above the national average when it comes to connection and community building. In Houson, 71% of respondents said they highly support integrated communities, versus the national average response of 63%. And one in two Houstonians said they frequently have cross-group interactions, compared to the national average of 41%.

What’s stopping us from connecting?

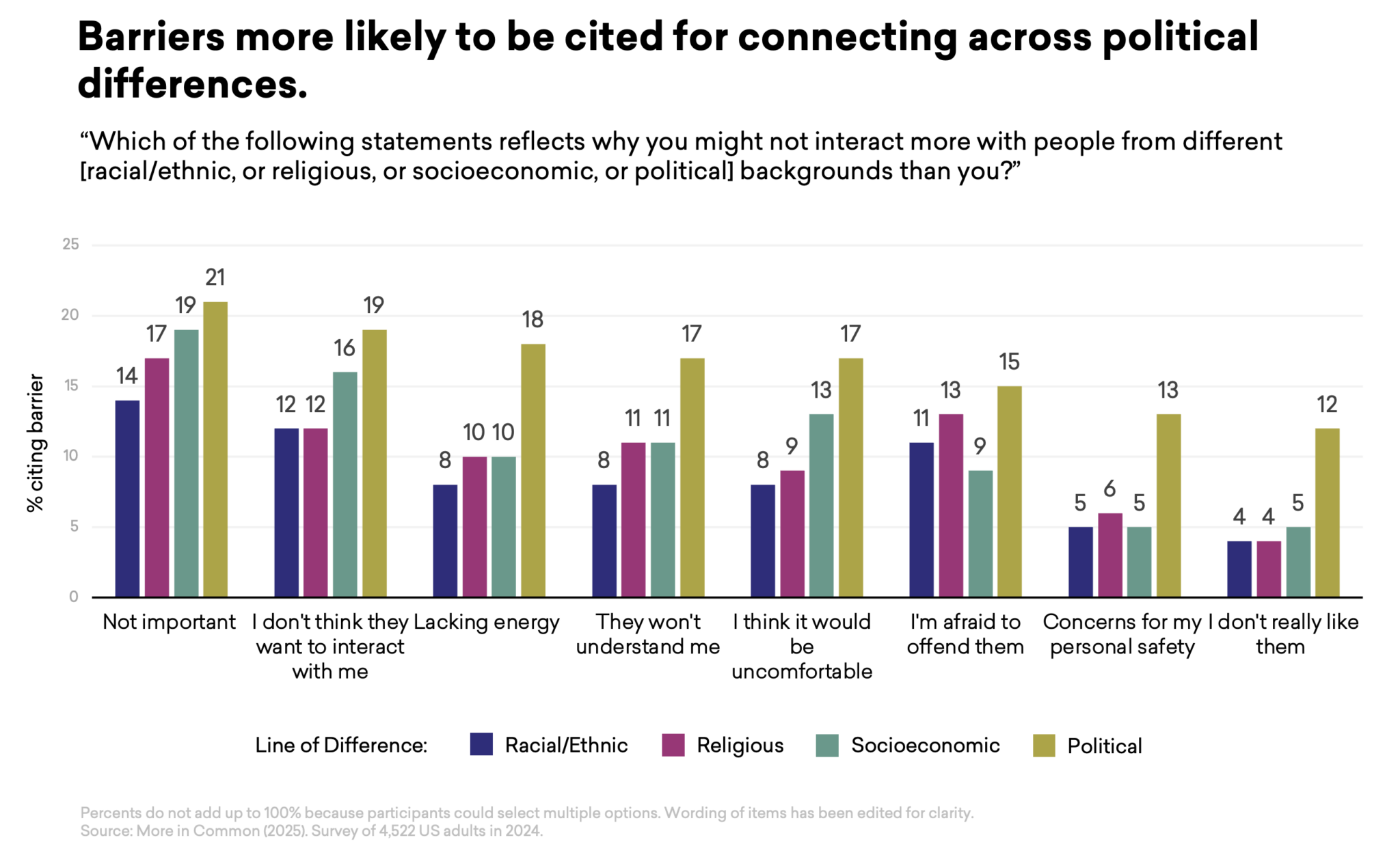

Politics is one barrier. Americans are most anxious about connecting across political differences, when compared to other areas. As the report summarizes:

Americans are also more likely to report personal hesitations (rather than a lack of opportunities) when it comes to connecting across politics. For example, they say that they “don’t have the energy” (18%), they think it would “be uncomfortable” (17%), or that they would “be misunderstood” (17%). People were also more likely to cite “concerns for my personal safety” (13%) as a challenge to connection across political lines of difference.

A deeper look at the data suggests high levels of intellectual humility are the strongest predictor of interest in connecting across political differences compared to others: “This suggests that people who are more willing to question their own beliefs are also more open to engaging with others who hold different political views.”

That said, according to More in Common, the biggest barrier to the kinds of connection Americans crave isn’t unwillingness, but lack of access. People are increasingly living in racially, religiously, and economically homogeneous neighborhoods. Add to that the shift toward online life—shopping, working, even worshipping virtually—and we are simply encountering fewer moments where differences might occur.

That’s why initiatives like Hello Neighbor are so important. The Pittsburgh-based nonprofit supports refugee and immigrant families as they rebuild their lives in the U.S. Through mentorship programs that pair local residents with newly arrived families, the organization fosters meaningful connections and mutual understanding.

Since its launch in 2017, Hello Neighbor has supported over 3,500 individuals from 58 countries throughout and beyond the critical first 90 days of resettlement. In addition to mentorship, they offer services like housing help, job support, and cultural orientation. One refugee family tells More in Common researchers, “When we get together, it is the best of times because we are like one family.”

A Hello Neighbor internal study revealed that after being involved with Hello Neighbor, 97% of volunteers advocated for refugee issues, 79% shared positive experiences with their networks, and participants built more diverse social connections. These efforts have reduced polarization in their communities (according to 93% of volunteers)—and, of course, made 100% of refugees feel more welcome.

Beyond lack of opportunity, Yudkin identifies two psychological dynamics that predict people’s willingness to connect. Intergroup anxiety (a fear of awkwardness or discomfort when engaging with someone different) was one strong negative predictor. And perceived social norms (belief that others in your community value cross-group connection) is another. Together, these insights point to promising levers for change: reduce intergroup anxiety and increase visible norms that make connection feel expected and valued.

The report does have some limitations to keep in mind.

One is self-reporting: The data reflects what people say they feel or do—not necessarily their actions. Though prior research suggests self-reporting is generally reliable, this is a key limitation. There’s also social desirability bias: People may overstate their willingness to connect because it sounds good. However, even when controlling for this bias, the findings remain strong. Finally, the deep dives into Houston, Pittsburgh, and Kansas City offer rich insights—but expanding to more diverse locales would give us a better picture of what’s going on.

Key strategies to foster connection

The report identifies powerful strategies to help individuals and organizations foster connection across race, class, politics, and religion in America.

1. Create more opportunities for connection cascades. The most common barrier to connection is simply lack of opportunity. Connection can emerge organically in spaces where people already gather—like schools, faith institutions, and community events—or through intentionally designed environments such as public parks and mixed-income housing. Once sustained, bridging experiences will inspire people to re-engage and help others do the same.

2. Strengthen norms of connection and promote connective responsibility. Most Americans see cross-group connection as a moral responsibility. Leaders can reinforce this by tying it to stories of national progress and civic strength. When people believe their communities value cross-group relationships, they’re more likely to connect. Local leaders, media, and institutions can shape these norms by highlighting successful collaborations and modeling inclusive behavior.

3. Foster a sense of belonging. People who feel they belong in their community are more open to connecting across differences. This means creating inclusive spaces where all residents feel respected and empowered to contribute.

4. Emphasize shared goals. Programs built around common interests—like improving the community—are more effective than those focused on discussing differences. A shared mission often motivates broader participation.

5. Reduce intergroup anxiety. Many avoid connecting out of fear of discomfort. Correcting misperceptions such as “the other side doesn’t want to connect” and building skills for navigating differences can ease this anxiety.

The report reminds us that connection isn’t just good for us—but it’s good for society as a whole. And the demographics who are most vulnerable to harm are most willing to engage and reconnect across divides. They aren’t fearful they’ll lose their identities—they’re hopeful we’ll rediscover our shared ones. As Niana, a 51-year-old liberal Black woman from Texas, says: “Surrounding yourself with people who are different than you—that’s how you grow. That’s how you learn from each other.”