“Everything Was Changed Forever” | Dickinson College

Dickinson Alumni & the Vietnam Experience

by Tony Moore

In recent months, we heard from several alumni looking to share their stories of serving in the Vietnam War. So to honor the upcoming 50th anniversary of the end of the war, and in our efforts to honor the experiences of Dickinson alumni who served, we put out an open call for stories. We were fortunate to receive several compelling narratives from alumni who shared their unique perspectives. Each story contributes to a richer understanding of the diverse experiences of Dickinson graduates during this significant period in history.

Some stories are best told in the voices of those who experienced them. Such as these.

Background: Nov. 1, 1955, to April 30, 1975 (although a peace agreement was signed in January 1973) The Vietnam War was primarily caused by the conflict between the communist government of North Vietnam, supported by the Soviet Union and China, and the noncommunist government of South Vietnam, backed by the United States. This struggle was rooted in the desire of North Vietnam to unify the country under a communist regime, while the U.S. aimed to prevent the spread of communism in Southeast Asia, subscribing to the domino theory that suggested if one country fell to communism others in the region would follow.

For the print version of this story, accounts were edited for space, some of them greatly. Following are fuller versions. Plus, learn more about Dickinson’s newly launched Military Veterans Network.

CLASS OF 1956

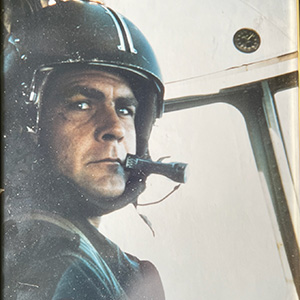

John Swift ’56: The Grunts & the Aviators

In July 1965, I had just completed the Army’s Infantry Officer Advanced Course at Fort Benning, Georgia. Although I was an Army aviator (fixed wings only), I was assigned to and deployed to Vietnam with the 1st Air Cavalry Division’s 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry. This was Lt. Col. (later Lt. Gen.) Hal Moore’s unit (of We Were Soldiers Once … and Young fame). Later on in November, now as the battalion’s headquarters company commander, I participated in the Plei Me, Ia Drang Valley, LZ X-Ray and LZ Falcon battles in the Pleiku campaign, for which the division was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation. In January 1966, I applied and received orders for an in-country transition into the CV-2 Caribou—the army’s twin-engine troop-cargo transport airplane. From that point on, I flew into just about every type of airfield—from the 1,000-foot dirt strips with trees on one or both ends at Special Forces camps in the Highlands to Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut. Essentially, I saw the war from two perspectives: the grunts and the aviators. The latter experience paved the way on my return for a very rewarding career as an American Airlines captain, piloting B-707, B-727 and DC-10 aircraft. In retrospect, I am certainly proud of my service in Vietnam, then and now.

In July 1965, I had just completed the Army’s Infantry Officer Advanced Course at Fort Benning, Georgia. Although I was an Army aviator (fixed wings only), I was assigned to and deployed to Vietnam with the 1st Air Cavalry Division’s 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry. This was Lt. Col. (later Lt. Gen.) Hal Moore’s unit (of We Were Soldiers Once … and Young fame). Later on in November, now as the battalion’s headquarters company commander, I participated in the Plei Me, Ia Drang Valley, LZ X-Ray and LZ Falcon battles in the Pleiku campaign, for which the division was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation. In January 1966, I applied and received orders for an in-country transition into the CV-2 Caribou—the army’s twin-engine troop-cargo transport airplane. From that point on, I flew into just about every type of airfield—from the 1,000-foot dirt strips with trees on one or both ends at Special Forces camps in the Highlands to Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut. Essentially, I saw the war from two perspectives: the grunts and the aviators. The latter experience paved the way on my return for a very rewarding career as an American Airlines captain, piloting B-707, B-727 and DC-10 aircraft. In retrospect, I am certainly proud of my service in Vietnam, then and now.

I do have trouble even at this advanced stage of my life (i.e., 90+) reconciling the anti-war movement that evolved shortly after my return. I am unable to forgive this disloyalty to country and its armed forces and by its perceived disunity, ultimately prolonged the conflict. I’m convinced that this behavior has metastasized into the unrest so prevalent in our society today. In response, I like to refer people to my favorite poem: “In Flanders Fields” from WW1 to the 3rd stanza “… to you from failing hands we throw the torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die (with those that have died) we shall not sleep though … poppies grow …”

CLASS OF 1963

Keith Phillips ’63: Tanks & Jeeps

Dickinson was the only college I applied to—heresy today, I know. Was then, too. I came from a lower middle class family living in a western Sussex County, Delaware, small town. The town and most of its inhabitants were parochial, under-educated, and racist. I had a lot to learn about a lot of things at Dickinson. Only one person from both sides of my family (my mom) had graduated from high school. I was shy, awkward and had very little self-confidence.

Dickinson was the only college I applied to—heresy today, I know. Was then, too. I came from a lower middle class family living in a western Sussex County, Delaware, small town. The town and most of its inhabitants were parochial, under-educated, and racist. I had a lot to learn about a lot of things at Dickinson. Only one person from both sides of my family (my mom) had graduated from high school. I was shy, awkward and had very little self-confidence.

In my senior year at Dickinson, I was the ROTC battalion executive officer and graduated as a Distinguished Military Graduate, receiving a commission in the Army as an armor officer. Dickinson was my life preserver. I spent three years in a tank battalion in Germany. I started out as a platoon leader and, as a very junior captain, was battalion operations officer. When I returned to the U.S., I went to the Infantry Officers Career Course at Fort Benning and after graduation was assigned to a light infantry battalion: 4th Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, 199th Light Infantry Brigade. After Vietnam, I was an instructor in the ROTC detachment at Marquette University. And then I resigned my commission.

There’s a story about a jeep. … Light infantry units were light on equipment, including vehicles. We had only one jeep for the S-4 (Logistics) section, which was not enough. I casually made the comment to one of the guys who worked with me that we could use another jeep. Three days later, a jeep appeared. I never asked where it came from. They had also had the seat cushion painted with the armor insignia (my branch), and I discovered that their nickname for me was Daddy, thus the name “Daddy’s Wagon” was on the hood. They were great guys.

Jerome “Jerry” John ’63: Bravery, Morale & Meeting My Future Wife

In July 1967, I was a captain in the Army Medical Service Corps, and, recognizing I would have to go to Vietnam at some point, I volunteered to go. No problem! Within 30 days, I was there. The most exciting thing that happened to me was at the start of the Tet Offensive in 1968, when the Viet Cong simultaneously blew up a number of nearby ammunition storage pads. We glanced outside before diving into shelter and saw a large mushroom cloud rising. We wondered if it was a nuclear bomb. (It wasn’t.) The most depressing thing was when I visited a coworker in the adjutant general’s office. He showed me a huge room filled with duffle bags and suitcases. They were waiting for a field-grade officer (major or higher) to certify the soldier was deceased before the belongings could be sent back to their family. So many.

The best thing was meeting a beautiful Vietnamese girl just after Tet. After I left Vietnam in August 1968, we corresponded for the next year. I flew back to Vietnam in 1969 as a civilian and accompanied her back to the U.S. for a one-month visit. Two years later, we were married on my sister’s front lawn in Honolulu. We’ve now been happily married for 53 years! We have one daughter. I was very fortunate. Too many weren’t. The bravery and morale of wounded soldiers would bring most people to tears. The medical people at every level were incredible.

CLASS OF 1964

Rodger McAlister ’64: Hot Zone Rescue

I was a first lieutenant and was flying Charlie model Huey gunships with the 2/20th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division, out of An Khe, South Vietnam. Covering troop insertions was our “bread and butter mission.” We would meet with the lift ships on their way to the landing zone and we would fly about 1000 feet ahead of the flight. As a team of two gunships, we would fire one pair of rockets at a time around the landing zone as we flew one aircraft on each side of the lift ships. We would fire our rockets into bushes, tree lines or anywhere that we felt the enemy could be lurking. As the lift ships would touch down, we would fly what we called a “daisy chain” to cover the landings. A daisy chain being one aircraft firing as the other circles around to cover the landing zone again.

I was a first lieutenant and was flying Charlie model Huey gunships with the 2/20th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division, out of An Khe, South Vietnam. Covering troop insertions was our “bread and butter mission.” We would meet with the lift ships on their way to the landing zone and we would fly about 1000 feet ahead of the flight. As a team of two gunships, we would fire one pair of rockets at a time around the landing zone as we flew one aircraft on each side of the lift ships. We would fire our rockets into bushes, tree lines or anywhere that we felt the enemy could be lurking. As the lift ships would touch down, we would fly what we called a “daisy chain” to cover the landings. A daisy chain being one aircraft firing as the other circles around to cover the landing zone again.

I got a call from the ground unit saying, “We’ve got three bleeders here, and Doc can’t get ’em stopped.” Our company policy was that no gunship was to land in a hot landing zone. I looked around inside the aircraft at the copilot, crew chief and door gunner; they all gave me a thumbs-up. We took 17 hits in the tail boom and rotor blades on that rescue, but no one in the aircraft, not the crew nor the patients, was hit. I’m thinking that we took them to the MASH unit at LZ English. As soon as we landed, they had three gurneys ready and they ran with the patients into the hospital tent. All three survived. As we are getting ready to lift off, this sergeant comes out and says, “Sir, I got your tail number, but I need your call sign for my records.” I reached out and grabbed the top page of his clipboard. I crumpled the paper in my hands as I told him, “I was never here!”

Jim Woodring ’64: Transporting a Captive (or Not)

While at Dickinson, I was in ROTC. At graduation I was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army and had a two-year service obligation. I selected military intelligence as my specialty (no, “military intelligence” is not an oxymoron). After graduating from Dickinson, I attended and graduated from Yale Law School. I began my military service by attending the Infantry Officers Training Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, and then I attended the Military Intelligence School at Fort Holabird, Maryland.

While in Vietnam I was assigned to the Phoenix Program (1968-69), created to identify and neutralize the leadership of the Viet Cong. The Saigon office of the Phoenix Program received information that a Viet Cong leader had been captured. Our colonel decided he should be brought to Saigon, where he could be interrogated. I was assigned to bring the captive to Saigon. To do this I had use of the station chief’s plane and pilot. The station chief was the ranking CIA officer in Vietnam. I asked the colonel what I should do if the captive attempted to escape. He answered, “Shoot him.” We landed on a dirt field and waited for the captive to be brought to the plane. Nothing happened. The jungle surrounding us was very quiet. We were unable to make contact with the district office where the captive was being held. The pilot said he felt very uneasy and he wanted to leave. That was fine with me, so we flew back to Saigon. We found out later the district office had come under attack, preventing the delivery of the prisoner to the plane.

Jim earned a Bronze Star and the Vietnamese Police Medal.

CLASS OF 1965

Ron Friedman ’65: The Transition Home

One day I got notice that I was to prepare to leave Vietnam. As the plane took off, there was a spontaneous cheer among the returning service personnel. Then the plane turned quiet, and for the next 20 hours or so there only were muted whisperings. On the flight back to the States, I thought that it was going to be an easy transition from Vietnam to civilian life. I had assumed that it was going to be like changing the channel on a television set. I gave no thought to it initially, but soon I was to discover that everything was changed forever. When the United States coastline appeared and when the plane landed, silence prevailed. There was no joy at returning, only relief.

After an all-night flight across the country, I landed at a small airport about 30 miles from my hometown. My parents were there to meet me. I dutifully shook hands with my father and kissed my mother’s cheek. They were visibly relieved. They passed a knowing glance between themselves. Looking back, I know now that they did not know what to say. They had heard the stories about the men returning from Vietnam. The anti-war protests had already directed anger toward the veterans. They really did not want to know anything about what had happened to me. My being tired saved them. And it saved me also. I was so relieved that I did not have to explain anything about my experiences. We rode in silence. That mutually imposed silence about my Vietnam experience lasted more than 40 years. They have both passed away, and I never will know exactly what they thought about their son or his experiences.

Ange Romeo ’65: Making Connections

Started with my flight from California to Vietnam. On the same plane was Dean Kilpatrick ’66, a Green Beret who would see and endure more than one person should. When we landed in Bien Hoa, we wished each other luck and left for assignments. Six months later, I learned that Dean was in Da Nang, so I flew there and spent a day and night with Dean drinking Heineken and listening to Cream sing “White Room,” “Sunshine of Your Love,” etc. Two other times I was visited in Vietnam by Alpha Chi Rho fraternity brothers Ray Scurfield and Jack Schultz. Ray was my freshman roommate in Morgan Hall, and Jack was my second semester senior year roommate in the old Crow House.

Started with my flight from California to Vietnam. On the same plane was Dean Kilpatrick ’66, a Green Beret who would see and endure more than one person should. When we landed in Bien Hoa, we wished each other luck and left for assignments. Six months later, I learned that Dean was in Da Nang, so I flew there and spent a day and night with Dean drinking Heineken and listening to Cream sing “White Room,” “Sunshine of Your Love,” etc. Two other times I was visited in Vietnam by Alpha Chi Rho fraternity brothers Ray Scurfield and Jack Schultz. Ray was my freshman roommate in Morgan Hall, and Jack was my second semester senior year roommate in the old Crow House.

Losing new friends was difficult. But going to the Salt Flats and watching the unearthing of hundreds of Vietnamese men and boys was awful. They had been captured by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers during Tet, marched to the Salt Flats and executed. As each body was dug up you would hear wailing from the mothers, wives and daughters who identified them. Prayers, chants, crying, thoughts of fathers, sons and brothers. Met some wonderful people. Proud of most of them, understood the others.

Michael Nemec ’65: 11 Months & 27 Days

As I was the junior officer in the FSA, I would hitch a ride on any aircraft going to Cam Rahn to pick up the pay for the troops. Our crew was paid once a month and had one day off. I got to see a lot of the country from the air in just about every aircraft the military was using. Vietnam is picturesque, even with the scars of war.

As I was the junior officer in the FSA, I would hitch a ride on any aircraft going to Cam Rahn to pick up the pay for the troops. Our crew was paid once a month and had one day off. I got to see a lot of the country from the air in just about every aircraft the military was using. Vietnam is picturesque, even with the scars of war.

On or about January 20, 1968, my replacement arrived in Vietnam on LZ Betty. I changed into my khaki uniform and raincoat to get a ride to Cam Ranh, where I would board a plane to the USA and return my issued M-14. As I would be flying over hostile land, I put two loaded magazines in the pockets of the raincoat. Upon arrival at the Air Force airfield, I met a fellow that I had met on my trip to Vietnam. We began drinking and sharing our stories. While I assumed that I would stay at the airport that night, I was surprised by a private calling me to board a plane. Although I had consumed a lot of liquor not available or permitted at LZ Betty, I jumped up to board the plane. As we arrived at the Seattle-Tacoma airport and U.S. Customs, I remembered the magazines in the raincoat. I turned to ask the officer behind me for a suggestion. He told me to keep my hands in my pockets with the magazines. I got through Customs and was free to fly home to Pittsburgh. My 11 months and 27 days of foreign service was over.

Bob Mumper ’65: From Fancy Wineglasses to Whiskey Straight

I was commissioned in the Marine Corps at my Dickinson graduation in 1965, along with fellow Army ROTC cadets. I was sent to Vietnam in March 1966 and served as the supply officer for the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines. One night, l ended up missing the chopper returning to the Da Nang naval hospital and had to spend the night aboard a ship. Life was quite different for Navy officers. Dinner was always served in the officers’ mess with white tablecloths, fine China and fancy wineglasses by waiters dressed in short-jacketed tuxedos. The food was high class and tasty. The naval officers were awed by the fact that I was a Marine officer in their presence and as a result “must have really been in the shit,” considering the fact that my utility uniform was pretty grungy and I was carrying my .45 caliber pistol.

I was commissioned in the Marine Corps at my Dickinson graduation in 1965, along with fellow Army ROTC cadets. I was sent to Vietnam in March 1966 and served as the supply officer for the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines. One night, l ended up missing the chopper returning to the Da Nang naval hospital and had to spend the night aboard a ship. Life was quite different for Navy officers. Dinner was always served in the officers’ mess with white tablecloths, fine China and fancy wineglasses by waiters dressed in short-jacketed tuxedos. The food was high class and tasty. The naval officers were awed by the fact that I was a Marine officer in their presence and as a result “must have really been in the shit,” considering the fact that my utility uniform was pretty grungy and I was carrying my .45 caliber pistol.

After dinner movies were shown supplemented by beer and snacks. Then I got to take a real shower with hot water and sleep in a real bed with clean sheets. It was like heaven. Once, I bunked in the same quarters with a surgeon. He had whiskey in his room, and he guzzled it straight out of the bottle. He showed me all of the before-and-after pictures of the surgeries and amputations that he had performed. All of the pictures were pretty gruesome. I could understand why he drank so much.

CLASS OF 1966

John Euler ’66: Courtroom Experience

After graduation from Georgetown Law Center in 1969, I joined the Marines. I was sick of school, curious about Vietnam and attracted by the training, leadership reputation and general ethos of the Marine Corps. After basic officer training, I was certified as a judge advocate in the summer of 1970. I volunteered for Vietnam and was assigned to a command in Da Nang, where I served until the following April. My primary duties involved the defense and prosecution of courts-martial. I did not experience a significant amount of combat. My son was born while I was deployed, and I returned home in August of 1971 following a couple of months in Okinawa. For a trial lawyer, the experience was an excellent way to learn how to work in the courtroom. I remained in the Marine Corps Reserve for 30 years, retiring as a colonel in 2000.

After graduation from Georgetown Law Center in 1969, I joined the Marines. I was sick of school, curious about Vietnam and attracted by the training, leadership reputation and general ethos of the Marine Corps. After basic officer training, I was certified as a judge advocate in the summer of 1970. I volunteered for Vietnam and was assigned to a command in Da Nang, where I served until the following April. My primary duties involved the defense and prosecution of courts-martial. I did not experience a significant amount of combat. My son was born while I was deployed, and I returned home in August of 1971 following a couple of months in Okinawa. For a trial lawyer, the experience was an excellent way to learn how to work in the courtroom. I remained in the Marine Corps Reserve for 30 years, retiring as a colonel in 2000.

John Bolan ’66: On Returning

I was an adjutant and S-1 officer in the Combat Intelligence Battalion, 1st Infantry Division, stationed in Lai Khe in 1968. I came back from the war and joined the protesters. My family had eight members fight in WWII, and I had to explain to them the difference in the wars and why our war in Vietnam was so wrong. I was able to return in 2011. Nice to see the country at peace. The people I met were very kind.

I was an adjutant and S-1 officer in the Combat Intelligence Battalion, 1st Infantry Division, stationed in Lai Khe in 1968. I came back from the war and joined the protesters. My family had eight members fight in WWII, and I had to explain to them the difference in the wars and why our war in Vietnam was so wrong. I was able to return in 2011. Nice to see the country at peace. The people I met were very kind.

Photo caption: My favorite picture from Vietnam. A few of us officers took kids from a local orphanage to the beach at Cam Ranh Bay. The beach is now bordered by big Western chain hotels. Michelle, my first child, was born while I was stationed in Vietnam. She still reminds I wasn’t present at her birth.

John Winfield ’66: From Vietnam to Carlisle

I missed the application deadline for college in 1959, so my father gave me three choices: to join the Army, Navy or Marines. I chose the Army and enlisted in September of 1959 for a three-year tour. A highlight of my six months in Saigon was getting knocked out of bed early one morning by the sound and concussion of bombs close to us. Hurriedly dressing I, like my fellow bunk-mates, headed up the stairs to our rooftop NCO Club where we watched two renegade pilots from the Vietnamese Air Force trying to bomb the Presidential Palace. Tanks were rolling down the street towards us and firing machine guns at the planes. Our building was in the middle… Mayhem erupted on the roof when everyone realized that the roof was a very dangerous place. You must imagine what it looks like to see 50 or so young men all trying to squeeze down a narrow stairwell at the same time.

I missed the application deadline for college in 1959, so my father gave me three choices: to join the Army, Navy or Marines. I chose the Army and enlisted in September of 1959 for a three-year tour. A highlight of my six months in Saigon was getting knocked out of bed early one morning by the sound and concussion of bombs close to us. Hurriedly dressing I, like my fellow bunk-mates, headed up the stairs to our rooftop NCO Club where we watched two renegade pilots from the Vietnamese Air Force trying to bomb the Presidential Palace. Tanks were rolling down the street towards us and firing machine guns at the planes. Our building was in the middle… Mayhem erupted on the roof when everyone realized that the roof was a very dangerous place. You must imagine what it looks like to see 50 or so young men all trying to squeeze down a narrow stairwell at the same time.

One day I received a letter from my father. My parents never knew where I was for the entire time that I was in Vietnam. When I opened the letter and read, my dad told me that I had a letter of acceptance. I was going to be able to go home to go to college … at Dickinson. I arrived on campus in the fall of 1962. I had never been to Carlisle. A taxi dropped me off at the center entrance to the quadrangle with a duffel bag of my stuff. I walked over to and up the steps into Old West through the front entrance, interrupting a faculty reception. I was politely pointed to the registrar’s office. As I climbed the stairs to my dorm room in East College, I passed the RA’s room, door open. The minute he found out that I was a veteran, he asked could I buy him a six-pack. I had arrived at college. I joined the Carlisle VFW. I was the youngest one in the club. None of the other vets had even heard of Vietnam. They soon would know otherwise. Everyone would.

Photo caption: Me in 1962 at our NCO club celebrating my promotion.

CLASS OF 1968

Richard Mohlere ’68: Casting a Pall

In the spring of 1968 as graduation approached, I received notice from my draft board to schedule a pre-induction physical shortly after school ended. This cast a real pall over what normally would have been a joyous season. For me, it was the only topic of conversation. Forget business interviews, graduate school and summer vacation. Coming from a military family, I faced a difficult decision: accept the draft and have no control over my future or enlist. I chose to enlist in the Army Officer Candidate program. It offered a training period of at least 10 months and an idea where I would be. I thought maybe the war might end by then. Bad guess! I was assigned as an advisor to a Vietnamese Army unit whose commander was my counterpart. He was twice my age, and through his eyes and experiences I saw the futility of our mission. The local population and soldiers cared only for the local hamlet, a hectare of rice paddy and their family. I don’t think my efforts had any lasting impact.

In the spring of 1968 as graduation approached, I received notice from my draft board to schedule a pre-induction physical shortly after school ended. This cast a real pall over what normally would have been a joyous season. For me, it was the only topic of conversation. Forget business interviews, graduate school and summer vacation. Coming from a military family, I faced a difficult decision: accept the draft and have no control over my future or enlist. I chose to enlist in the Army Officer Candidate program. It offered a training period of at least 10 months and an idea where I would be. I thought maybe the war might end by then. Bad guess! I was assigned as an advisor to a Vietnamese Army unit whose commander was my counterpart. He was twice my age, and through his eyes and experiences I saw the futility of our mission. The local population and soldiers cared only for the local hamlet, a hectare of rice paddy and their family. I don’t think my efforts had any lasting impact.

CLASS OF 1971

Pam Rich Estes ’71: A Challenging Time

I was married to William Pierce Gunter ’71, who served in Vietnam from April 1969 to December of 1970. Bill was a first lieutenant in the 82nd Airborne who parachuted with his men into places where the Viet Cong had been spotted. He was awarded the Bronze Star and several Purple Hearts. The Bronze Star was reserved for those who distinguished themselves by heroism, outstanding achievement or other meritorious service. Bill was a member of Phi Kappa Sigma. He died in 1982. (Bill suffered from) post-traumatic stress disorder, which was not truly understood at that time but certainly affected those putting themselves and their comrades in danger repeatedly during what we now recognize as a war we could not win. I appreciate the opportunity to give this information to you, and I trust that your handling of it will give a fuller picture of a difficult and challenging time in our county.

I was married to William Pierce Gunter ’71, who served in Vietnam from April 1969 to December of 1970. Bill was a first lieutenant in the 82nd Airborne who parachuted with his men into places where the Viet Cong had been spotted. He was awarded the Bronze Star and several Purple Hearts. The Bronze Star was reserved for those who distinguished themselves by heroism, outstanding achievement or other meritorious service. Bill was a member of Phi Kappa Sigma. He died in 1982. (Bill suffered from) post-traumatic stress disorder, which was not truly understood at that time but certainly affected those putting themselves and their comrades in danger repeatedly during what we now recognize as a war we could not win. I appreciate the opportunity to give this information to you, and I trust that your handling of it will give a fuller picture of a difficult and challenging time in our county.

Read more from the fall 2024 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published November 20, 2024